This time last year I was preparing to wrap up at university.

Now I’m writing up, essentially, a dev blog.

I’m a developer working for a company called Ultimerse. We dabble in a few things here and there, but have just begun our foray into the games industry, leading with our first VR project, Paperville Panic.

Paperville Panic is a game with, well, panicked paper… for the most part.

Elevator pitch; you’re a firefighter and things are both highly unstable and highly flammable at all times - mix in a paper society who doesn’t know any better and you have yourself an idea of our game.

This is a world of firsts for both the company and its members. One thing everyone on the project shares is the fact that it’s our first time working in VR, and that can lead to the majority of our major problems, so as a lighthearted introduction, here’s a list of things we have experienced and learnt from in the crash-course that is the first 6 months of our development cycle.

1. Prototype

This is oversaid and underheard, and goes for all projects, not just VR.

Everything needs to start at a prototype.

Need more specifics? Let’s delve.

A good game is often one with a solid foundation of simple techniques, if it doesn’t work at a base level with simplistic controls, its probably won’t work once you start buffing it down and polishing it back up. In VR this part is vital, because when somebody inevitably starts thinking “This isn’t bad, bad - it could just use something more” you encounter the problems of ‘Where to put that cool new thing’. The thoughts often go somewhat like this,

- Lets add ‘x’ character function to improve that. What key can you bind it to?

- Right, well what about a tool that does it for you? How do we avoid cluttering the toolbelt?

- Can we have an inventory? Well of course we can, but how do we flow from our current looks to one that can allow pop ups that go with that system?

And at some point, with much deliberation, you either think of a great solution, or work around the problem.

This will happen one way or another, but is worsened to the nth degree if you don’t begin with that solid foundation we spoke of earlier, so prototype. Prototype, playtest the prototype, play it yourself, play the prototype until you can't do anything but see its flaws, and when those flaws seem trivial, you have a nice slab of concrete to build on. Or biscuit, if you are more of a cheesecake guy.

B. Take some time to experiment with new tech.

This is VR! The world is your oyster, even literally if you want to make a game about aquatic life (send me screenshots though).

Being excited to start your new project is fine, it’s a good thing, but before you start getting deep into the nitty gritty, take a week and do research. Take another week and just think about cool stuff. Nobody has time to innovate once they are on a tight deadline, so use the time you have before the project begins to do try and set the next trend, be adventurous. For example, movement in VR is quite limiting right now, and most projects (ourselves currently included) are falling on teleportation to move around. When we were deciding on prototypes, we had ideas that revolved purely around abstract methods of movement, even if they didn’t get picked. Make a game that ships with a real set of monkey-bars, who cares! The ideas that you can leave with at the end of that time could definitely be worth more than what you put in. Successful innovation gives its own reward, just look at games like Climbey.

So take your time, the genre is new enough that there is still a fair chance you think of something no-one else has.

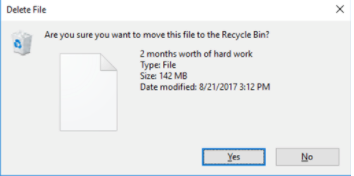

Three. Don’t get attached.

A simple fact of life in the industry, things need to be prepared to go in the trash at a moment's notice. I’m writing this blog right now, and afterwards it needs to be approved, and if it doesn’t, i’ll do it again. That happens, so don’t be surly Shirley, and try not to take it too personally, chances are the individual who asked you to move on has had to do the same thing at some point.

Saying all of this, the does NOT mean you shouldn’t put in the love your game needs and deserves, otherwise people will notice that too. Treat each asset you make like a child, love it and keep it clean. But when I say child, I don’t mean yours. I mean like, a cousin’s or something. I’m bad at analogies. The point is, at some point it might have to leave, so a healthy detachment is a good thing.

0100. Speaking of keeping it clean.

Please, for the love of god and meat pies, keep your work clean. Name things well, comment your code, freeze your transforms, and give things parent objects so the aren’t thrown lose all around the shop! You never know when someone else needs to take over your stuff. Whether it be a bug, or some modelling help, someone else could need to see your work, and if it’s as messy as my bedroom it will take a lot longer for them than it would have to make it tidy in the first place. Also, trying to attach an object to a script or vice versa takes so much longer when somebody's been too liberal in placing some ~200 objects in between them.

This also goes for the workspaces themselves. Don’t keep a collection of mugs on your desk, wipe down your Wacom after you use it, keep a packet of wipes for any especially sweaty playtests and everybody will thank you.

This one’s just housekeeping, sure, but do it anyway.

Finally. Make a friend.

The games industry is the biggest strength of the games industry. Everyone is helpful, close, friendly, and ready at a moment’s notice to give the help you might need. I mean, that’s why we write these dev blogs in the first place, so you can learn from our mistakes.

So go network! I was told by a very wise man that if you are dedicated to your networking, a programmer can easily live off of the free pizza and beer found at all these cool get-togethers. It’s much easier to get a foothold when you have people to give you a leg up. Hit up PAX, strike up a conversation (hopefully during their downtime, PAX, so I‘m told, can be very stressful), go to some talks from industry professionals and tell them they did a great job, and you could be glad that you did. Even if you don’t make a contact, the advice they give is valuable.

A throwaway tip; don’t reinvent the wheel.

Especially early in the prototyping phase, don't be afraid to use assets from the store, or a friend. And if eventually you decide you really can't use ‘x’, that doesn’t mean you have to reinvent the wheel, just make your own wheel but, I dunno, use an octagon instead of a circle.

DON’T DO THIS THOUGH.

You’ll find many more posts with more helpful tips like this within arms reach thanks to the power of Google.

Keep your eyes and ears out for Paperville Panic and more dev blogs.

Talk to you all soon, Aidan.

@aidanmckeowndev